https://doi.org/10.34024/prometeica.2024.31.19572

DESCREVENDO QUESTÕES DE MATEMÁTICA EM AVALIAÇÕES PARA PESSOAS COM DEFICIÊNCIA VISUAL

DESCRIBIR PREGUNTAS DE MATEMÁTICAS EN EVALUACIONES PARA PERSONAS CON DISCAPACIDAD VISUAL

Renato Marcone

(Universidade Federal de São Paulo, Brasil)

Rodrigo Bortolucci

(Fundação para o Vestibular da Universidade Estadual Paulista, Brasil)

Recibido: 02/10/2024

Aprobado: 20/11/2024

ABSTRACT

This work is a continuation of the previous research presented in MES 11 (Marcone & Bortolucci, 2021), where we were trying to understand the role of the ledor (reader), a person who reads the test to the visually impaired person during an assessment. The work carried since then and up to the second half of 2022, following the conclusions made in our previous work, was focused on the study, understanding and systematisation of the process of adapting items, those related to mathematics such as drawings, tables, graphs, statements, and everything related to the elaboration of mathematics questions, and the activity of the maths test ledor. For this purpose, interviews were carried out with three professionals directly linked to this type of activity, with extensive experience in the activity of adapting mathematical tests, in addition to the analysis of theoretical references on the subject. We will present the main points addressed in each interview, such as the need for the test adaptation process to occur simultaneously with the test construction, so that the necessary interventions can occur before the test assembly is completed, followed by a discussion, with conclusions showing how important it is to describe an image properly, with minimum information, so the candidate can achieve the test with the time they have. This research was evaluated by an independent ethics committee and authorised to be carried out.

Keywords: inclusive mathematical education. inclusive assessment. adaptation of teaching materials.

RESUMO

Este trabalho é uma continuação da pesquisa anterior apresentada no MES 11 (Marcone & Bortolucci, 2021), onde buscávamos entender o papel do ledor (leitor), pessoa que lê o teste para o deficiente visual durante uma avaliação. O trabalho realizado desde então e até o segundo semestre de 2022, seguindo as conclusões tiradas em nosso trabalho anterior, foi

focado no estudo, compreensão e sistematização do processo de adaptação de itens, aqueles relacionados à matemática como desenhos, tabelas, gráficos, enunciados e tudo relacionado à elaboração de questões de matemática, e à atividade do ledor de teste de matemática. Para tanto, foram realizadas entrevistas com três profissionais diretamente vinculados a esse tipo de atividade, com ampla experiência na atividade de adaptação de testes matemáticos, além da análise de referenciais teóricos sobre o tema. Apresentaremos os principais pontos abordados em cada entrevista, como a necessidade de o processo de adaptação do teste ocorrer simultaneamente à construção do teste, para que as intervenções necessárias possam ocorrer antes da montagem do teste ser concluída, seguido de uma discussão, com conclusões mostrando o quão importante é descrever uma imagem adequadamente, com o mínimo de informações, para que o candidato possa realizar o teste no tempo que tiver. Esta pesquisa foi avaliada por um comitê de ética independente e autorizada a ser realizada.

Palavras-chave: educação matemática inclusiva. avaliação inclusiva. adaptação de materiais didáticos.

RESUMEN

Este trabajo es una continuación de la investigación previa presentada en MES 11 (Marcone & Bortolucci, 2021), donde tratábamos de comprender el papel del ledor (lector), persona que lee la prueba a la persona con discapacidad visual durante una evaluación. El trabajo realizado desde entonces y hasta el segundo semestre de 2022, siguiendo las conclusiones extraídas en nuestro trabajo anterior, se centró en el estudio, comprensión y sistematización del proceso de adaptación de ítems, aquellos relacionados con las matemáticas como dibujos, tablas, gráficos, enunciados, y todo lo relacionado con la elaboración de preguntas de matemáticas, y la actividad del ledor de prueba de matemáticas. Para ello, se realizaron entrevistas a tres profesionales directamente vinculados a este tipo de actividad, con amplia experiencia en la actividad de adaptación de prueba matemáticos, además del análisis de referentes teóricos sobre el tema. Presentaremos los puntos principales abordados en cada entrevista, como la necesidad de que el proceso de adaptación del test se realice simultáneamente con la construcción del mismo, de forma que se puedan realizar las intervenciones necesarias antes de que se complete el montaje del test, seguido de una discusión, con conclusiones que muestren lo importante que es describir una imagen de forma adecuada, con la mínima información, para que el candidato pueda realizar el test con el tiempo del que dispone. Esta investigación fue evaluada por un comité de ética independiente y autorizada para ser realizada.

Palabras clave: educación matemática inclusiva. evaluación inclusiva. adaptación de materiales didácticos.

This work is a continuation of the previous research presented in MES 11 (Marcone & Bortolucci, 2021), where we aimed to explore the role of the ledor (reader), the person responsible for reading the test aloud to visually impaired (VI) candidates during an assessment. In that study, we wanted to understand not only the function of the ledor but also the ways in which their presence and actions could influence the VI candidate performance, by facilitating or complicating their task. Our focus was on identifying the specific types of interferences, both positive and negative, that could emerge during this process. For instance, while a well-trained ledor could enhance the candidate's understanding by clearly articulating the mathematical text, a ledor without this proper training could, unintentionally, commit mistakes and hinder the VI candidate’s performance, such as misreading mathematical symbols or graphs, leading to confusion or misinterpretation. Additionally, we examined how the ledor's voice tone, talking speed, and familiarity with mathematical content could influence the candidate’s ability to concentrate and

perform in a better way. This current research builds on those findings by further investigating this relationship between the ledor and the VI candidate, with the goal of systematizing best practices for training ledores and developing standardized guidelines that minimize the risk of unintentional bias or interference, ultimately ensuring a fairer and more equitable testing experience for visually impaired students.

The work carried out since then and up until the second half of 2022, building upon the conclusions of our previous research, has been focused on studying towards understanding the processes involved in the relationship between VI candidates and the ledor, as well as the process of adapting mathematical assessment items. These items include elements such as drawings, tables, graphs, and problem statements. Undoubtedly, the role of the ledor plays a central role on our analysis. The accuracy and efficiency of the ledor's work are vital in ensuring that these students receive equitable opportunities to demonstrate their mathematical knowledge under the same time constraints as their sighted peers, that is why we understand that the society in general addressing this issue is imperative.

To deepen our understanding of this adaptation process, we conducted interviews with three key professionals, all of them with an extensive experience in adapting mathematical tests for visually impaired candidates or teaching mathematics to VI students. These interviews were discussed and analysed under the light of literature concerning debrailization, meaning a change in reading culture among VI population, that are not learning Braille properly anymore, privileging screen readers. The first interviewee, Regina Fátima Caldeira de Oliveira, is the Braille text review coordinator at the Fundação Dorina Nowill para Cegos, a nonprofit organization in Brazil, and a member of both the Ibero- American and World Braille Councils. Regina’s perspective as a professional and as someone with visual impairment provided insights into the issue of adapting mathematical content. The second interviewee, Christiane Batista Penna, works at an institution that prepares and administers exams nationwide. She has been responsible for overseeing the adaptation of all entrance exams and assessments for over two decades, giving her extensive experience in navigating the complexities of test adaptations. Finally, Paula Marcia Barbosa, a teacher at the Benjamin Constant Institute (IBC) since 1982, brought forward her long-standing experience in educating visually impaired students in mathematics. The Benjamin Constant Institute (IBC), founded in 1854 by Emperor D. Pedro II, is a pioneering institution in Brazil dedicated to the education of visually impaired individuals. It provides services from early childhood stimulation through to the completion of fundamental education II, equivalent to middle school in the United States, where students are typically around 14 or 15 years old. Paula’s contributions were particularly important in highlighting how historical and contemporary practices intersect in the adaptation process.

In this paper, we will present the main points addressed in each interview, discussing and systematizing them into practices that could lead towards a more equitable assessment process. One of the most crucial findings is the need for test adaptation to occur alongside with the creation of the exam itself. By integrating adaptation early in the process, it allows for necessary adjustments to be made before the test is finalized, ensuring that accessibility considerations are an inherent part of the test design rather than an afterthought. This proactive approach can prevent issues that arise when adaptations are made later, which often limit the ability to make meaningful changes and ensure fairness.

Afterwords, we will present a discussion over the main points of these interviews, such as the importance of properly describing images and visual elements or providing clear, concise information with only the essential details, as it directly impacts the candidate’s ability to comprehend and respond to the test items within the limited time they are given. This is particularly relevant in mathematics, where visual complexity often presents significant challenges both to the ledor, who is usually not trained in mathematics, and the VI candidate.

Additionally, the paper will propose new practices, that could implicate on improving adaptation processes and contributing to a more equitable assessment for all, including the visually impaired candidates. The ethical considerations surrounding this research were carefully reviewed, and the study

was authorized by an independent ethics committee, ensuring that all protocols met the necessary standards for conducting this research.

Regina Fátima Caldeira de Oliveira is the braille text review coordinator at the Fundação Dorina Nowill para Cegos [Dorina Nowill Foundation for the Blinds] and a member of the Ibero-American Council and the World Braille Council. Fundação Dorina Nowill para Cegos is a nonprofit philanthropic organisation in Brazil. She was born with glaucoma and saw something until she was 7 years old. She arrived at the Dorina Foundation when she was 8 years and a few months old, and never left.

Regina started a discussion bringing her view, based on her professional and personal experience, as a blind person herself, that there is no concern on the part of evaluation boards in general to create a universal item, valid for all audiences, including visually impaired people. She pointed out that this concern may even exist, but that it is not observed in practice. In addition, according to her, the area of mathematics is certainly one of the most complex to adapt items to, because of its various elements (graphs, figures, tables, …) used in writing the questions.

The interviewee emphasised that the Braille language facilitates the adaptation of the tests, allowing it to be very close to the conventional version, since the Braille System has several adaptations and symbology, even for mathematics, already consolidated. However, there is a bottleneck in mathematics teaching for visually impaired (VI) students, in which access to Mathematics textbooks in Braille is infrequent. According to her experience, as a result of working on several fronts of Inclusive Education, there is a lack of books for these students with adapted items. She states that there are people arriving at college, studying mathematics, who do not know the Braille symbology, restricting the access of these VI students to teaching material.

This lack of knowledge means that the entire process of adapting mathematical items is completely based on the description of mathematical elements (expressions, graphs, figures, among others), which restricts communication with the student or candidate who will participate in an assessment. Regina narrates that, as a candidate in a selection process herself, when faced with a question adapted for the performance of a ledor, in which the five alternatives contained graphics, she gave up of that particular question, as she would not remember the description of the first alternative (A) when she was finishing listening to the description of fifth alternative (E).

This reinforces the need for the test adaptation process to occur simultaneously with the test construction, so that the necessary interventions can occur before the test assembly is completed. This is one of the most important conclusions of our study. This is a practice on trial at the National Institute of Educational Studies and Research Anísio Teixeira (INEP), in which the adaptation of tests takes place through joint work between specialists and an adaptation commission, which intervenes along the construction of the test. This is a practice that has not yet been properly established in the test adaptation stages carried out by other institutes, where adaptation usually occurs after the item is ready, reducing the possibility of necessary adjustments, limiting actions to make the test more comparable and fairer between VI and sighted candidates.

In general, the test adapted for the work of the ledor is still distant from the needs of a VI candidate, mainly due to the difficulty of ledores in dealing with the specificities of mathematical language, which entails the need for all the terms presented in the test to be extensively described. In the interviewee's conception, it facilitates the process of reading the items when the readers have training in the area of knowledge of the test they will read.

In addition to the practices adopted by most institutes, Regina also indicated that the difficulty of reading Braille with both hands makes reading very slow when compared to visual reading. Consequently, one

hour more in the total test time, as required by the Brazilian law, is not enough when it is entirely read in Braille.

Finally, Regina reported that as a candidate she felt uncomfortable/embarrassed to ask for the reading to be repeated by the ledor, even knowing that this was her right. In this, the implementation of a digital reading could contribute, as it would avoid this type of situation.

The second interviewee was Christiane Batista Penna, an employee of an institute which prepares and administers exams. She is responsible for preparing the adaptations for all entrance exams and assessments with more than 20 years of experience. She used to work on the Dorina Foundation. Christiane began by presenting a brief historical account of how the test adaptation process took place in recent years at her workplace.

She reported that Braille printers were acquired in 2010 for the institute where she works today and, from then on, the number of handmade adaptations made by the institute began to be reduced. Currently, the machinery is up to date, with more modern machines than those of 2010. Regarding test adaptations, the current standard is to use images adapted for VI candidates and use description only in cases where the image does not fit. Another option is for these specific cases to make the handmade adaptation. According to her, the difficulty of adapting often occurs for pictures of paintings, photos, or complex images, such as crossing lines, for example.

An important practice reported by Christiane is that, sometimes, the image is replaced by schemes or simplifications that allow the VI candidate to appropriate the idea in order to be able to answer the question. In cases where this adaptation is not possible, the replacement of the question is discussed. For example, in the computer science test it is common to suggest the exchange of questions that request the association of programs to their respective icons. In fact, after a series of recommendations, this type of question has been avoided. This is because the use of computers by blind people is different, since there is no visual recognition of the icons, as the computer informs the name of the program.

Christiane also said that she maintains contact with VI people to hear suggestions to improve the adaptation process and that a barrier to greater speed in the implementation of new adaptations is that she cannot talk to candidates after the end of the tests to get feedback on the quality of the adaptation offered. Consequently, this feedback on the quality of the adaptation of the test ends up occurring through the occurrence of appeals or judicial requests that the institute may receive. In the absence of this, it is understood that the adaptation was made satisfactorily. This shows how important research as this one is.

The interviewee currently makes some adaptations and descriptions of elements present in the mathematics items, however, depending on the complexity of what was proposed, she requests support from the items writing team, the people who create the questions, in this adaptation process. However, it should be noted that the group is not used to carrying out this type of activity and there is no manual with instructions for carrying out these adaptations. Therefore, there is a need to create material to guide this process of test adaptation.

Finally, it was highlighted that the Foundation where Christiane works complies with current Brazilian legislation with regard to test adaptations. The list of options for candidates is updated when a demand becomes frequent and is not foreseen in the announcement. The most recent update was on electronic calculator usage. Many applicants requested this. So, a rule is being studied to meet this demand without offering any privileges regarding the performance of the test. The main idea is to be equal.

In addition to a report made by Regina, Christiane stresses out that currently the VI student usually receives digital didactic material when they start attending regular school. The consequence of this is

that these students become more accustomed to the descriptions of figures than to reading Braille writing, which, as previously mentioned, already has consolidated adaptations in the area of mathematics.

The third interviewee was Paula Marcia Barbosa, teacher at the Benjamin Constant Institute (IBC) since 1982, an institute with a special school for visually impaired students founded in 1854 by the emperor

D. Pedro II. She graduated in Mathematics and post-graduated in Inclusive Mathematics Education. She teaches the subject Didactics of Mathematics in the Sequential Superior Course in the Area of Visual Impairment at IBC. In addition, she is a consultant and works directly with the adaptation of mathematics tests at INEP and at the Institute of Pure and Applied Mathematics – IMPA.

Right at the beginning of the conversation, Paula brought up the case of one of her students who felt harmed by a ledor who did not know mathematics, reinforcing the importance of recruiting ledores who know the particularities of the area of knowledge in which they will work. Then, she reinforced a speech of the other two interviewees, when commenting on an article that reported a drop in the number of students who knew and used the Braille System, which implies a greater need for the use of the ledor as a resource for adapting tests for blind candidates.

Regarding the test adaptation process, the interviewee commented on a common confusion between the term’s description/adaptation of test questions and audio description. According to her, the audio description includes a characteristic detailing that is bad for the description/adaptation of questions. When thinking about adaptation, the idea is to bring the minimum to the understanding of what is set. In addition, in the audio description they speak very quickly and in detail so that the blind person understands what is necessary in the necessary time, for a movie scene, for example. On the other hand, when describing/adapting questions, the speech must be short and direct, limiting itself to saying only what the person needs to answer the question.

Paula related some of her experiences and mentioned, for example, that INEP makes changes to the questions in order to render the images accessible to blind candidates. The changes made are introduced into the tests by all candidates, blind or not. Then, she commented on the use of Easy Braille as a resource for adapting tests, as it contains resources for making figures and mathematical elements. But this escapes the candidate who does not know Braille. In addition, when asked about what is most difficult to adapt, she pointed out three-dimensional figures and two-dimensional shapes within another, like a triangle inscribed on a circumference.

Then, she narrates some problems that she understands that hinder the performance of the blind candidate. According to Regina, many candidates who are used to the screen-reading feature abandon braille reading. This reiterates that the idea of developing software for screen reading, specific for tests adapted for VI candidates, may be the most appropriate resource, considering the equality of the process in future assessments. She also emphasises the importance of allowing the VI candidate to use soroban during the resolution of the tests, as this helps the process of “taking notes on the calculation”, not requiring the candidate to do all the processes mentally and not giving the candidate any privilege as the soroban will not calculate automatically as an electronic calculator would.

Regarding procedures, she stressed the importance of collecting complaints and suggestions from candidates and professionals involved with the cause to analyse and verify ways to improve the adaptation of the test, in addition to the creation of a committee for adapting tests that points out what is necessary to facilitate adaptation for the VI candidates and not facilitate the question. Finally, she pointed out that long tests should not be the responsibility of a single ledor, even more so if we consider that usually the candidate who requests a ledor ends up having an extra hour of testing.

The three interviewees highlighted a concerning trend: blind students are increasingly failing to learn Braille in schools due to the lack of materials adapted for this system. This absence of textbooks adapted in Braille and the lack of educational resources has forced many VI students to seek alternative tools to access information. Vieira (2022) also address this issue, noting that the growing reliance on screen readers has become a prevalent solution for blind individuals to access written texts. While these technologies have proven to be invaluable in many contexts, they present certain limitations and bring problems, such as students are forgetting how to write some words, because they are not reading them, only listening.

Visually impaired students usually argue that the main issue with Braille is the additional time required to complete tasks, even small ones such as reading a medicine leaflet, particularly when visually impaired individuals are unable to read with both hands. As this research has found, this factor further complicates the learning process, making it difficult for students to keep up with their peers. This raises questions about the long-term implications of relying more heavily on-screen readers, and whether this change is unintentionally marginalizing Braille as a literacy tool.

Although screen readers and Braille are essential resources for people with visual impairments, we agree with Vieira that a major concern is that screen readers are replacing Braille, instead of complementing it. Sousa (2015) raises a critical question: could the widespread use of digital tools lead to the underuse of Braille as a mechanical form of writing? This phenomenon, referred to as "debrailization" by Vieira (2022), may have consequences far beyond we see in the moment. The continued trend toward digital solutions may result in a reduced demand for Braille-based exams, leading to an increased dependence on ledores (human readers) or digital screen readers during assessments. This reading cultural change among blind community may offer some advantages, but, however, could ultimately undermine the accessibility and autonomy that Braille provides to visually impaired students. The challenge for educators and policymakers lies in finding balance between embracing technological advancements and preserving the fundamental role of Braille in fostering independence and literacy among visually impaired learners.

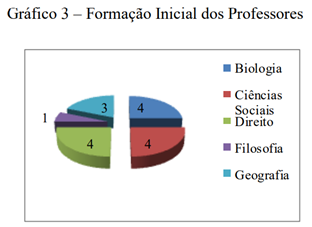

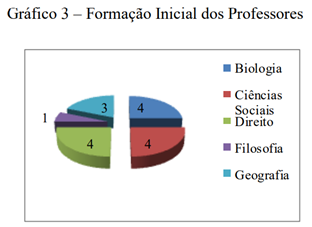

Another important point that the literature helped to clarify was the distinction between audio description and description of images and mathematical elements. Consider the following example, presented in Oliveira (2017), p. 126:

[Audio description: pie chart, divided into five pieces in the colours: blue, red, green, lilac and light blue. Each piece corresponds to the initial training of teachers. Thus, in Biology, four professors; in Social Sciences, four; in Law, four; in Philosophy, one and in Geography, three].

Note that audio description pays attention to details such as the colours shown in the graph. If this detail is unnecessary for transmitting the essential information to answer a question based on the graphic, then

there is no need for this detail to be present in the description of the image, if it is used in a maths test question. Below is a suggested description for this graph, in case it was present in a test:

[Description: Graph of sectors indicating the number of teachers organised according to their initial training, as follows: 1 Philosophy teacher; 3 Geography teachers; 4 biology teachers; 4 professors of Social Sciences and 4 professors of Law].

This concise character is one of the principles pointed out by Machado (2020) in the work of describing an image present in a question: the description cannot be so long and complex that it makes it difficult, or even unfeasible, to construct the answer to the question, or, as a consequence, the VI candidates would give up, as related by Regina in her interview. In addition to this, the author also brings as a principle that the description cannot lead (or reveal) the answer to the question linked to the image. The idea of these two principles is that they serve as a counterbalance, in order to bring what is essential for the resolution of the issue, but that also do not direct the candidate to the answer, facilitating the resolution. As mentioned before, this reinforces the need for the test adaptation process to occur simultaneously with the test construction.

Based on the data we have gathered; the next steps of our research are.

Developing guidelines for the training of ledores (human readers). These recommendations will focus on ensuring that ledores are adequately taught to assist VI candidates in a way that minimizes their interference, positive or negative. Proper training will focus on how one can read mathematical language

in a way one can reduce dubious interpretations, for example, a ledor could read �3 and √3 in the same

2 2

way and the VI candidate would not notice. This is not a mistake, but the choice of words could lead to a mistake. This is a crucial step toward mitigating the injustices that often arise when VI candidates are tested, ensuring that they have the same opportunities to demonstrate their knowledge as their sighted peers.

We also plan to organize workshops for those responsible for creating mathematics questions used in assessments, so they could think about these issues in advance, facilitating the work of the ledor. The focus will be on ensuring that all elements, from graphs to problem statements, are possible to be described in a way that is not only clear and concise but also accessible to VI candidates. This approach will contribute to a more equitable testing process, where VI candidates can engage with the content on an equal footing with sighted individuals, reducing the need for improvised adaptations.

A key aspect of our future work will be proposing a framework for the development of software and a protocol to administer tests to VI candidates without the need for a ledor. The idea is that this software would offer the necessaries descriptions and readings recorded in advance, reviewed by at least two mathematical professors, reducing the possibility of human error or bias. The development of such technology is particularly important, as the growing number of VI individuals entering higher education and the workforce is expected to exceed the availability of trained ledores in the medium term. By automating this process, we aim to create a more scalable, reliable, and independent system for administering assessments to VI candidates, thus reducing the reliance on human assistance while enhancing accessibility.

In conclusion, these steps are designed to address the urgent and the strategical, urgent meaning need for improved training for the ledores and strategical meaning the goal of creating systemic changes that promote greater accessibility in assessments though automatization and systematic process to create inclusive mathematical items in advance. By combining recommendations for ledor training, workshops for test designers, and the development of innovative testing software, our research seeks to ensure that VI candidates are no longer at a disadvantage during assessments, providing a more inclusive and equitable experience for all.

This research highlights the complex challenges of adapting mathematics assessments for visually impaired (VI) candidates, emphasizing the need for a more inclusive approach throughout the test development process. Through interviews with key professionals such as Regina Fátima Caldeira de Oliveira, Christiane Batista Penna, and Paula Marcia Barbosa, it became evident that current adaptations of visual elements like graphs, diagrams, and tables often fall short of fully meeting the needs of VI students. The difficulty lies not only in translating visual information into accessible formats but also in ensuring that the adapted material remains as close as possible to the original content in terms of fairness and clarity.

Regina emphasized that evaluation boards do not prioritize creating universal items that serve both visually impaired and sighted individuals. She highlighted the particular difficulty of adapting mathematics items due to the complexity of graphs, tables, figures and etc. Accordingly, to her, although the Braille system has well-established mathematical symbols, the lack of adapted textbooks for visually impaired students creates challenges. Many students reach higher education without mastering Braille mathematics, limiting their access to educational materials to audio techniques. This makes the adaptation process heavily reliant on oral descriptions of mathematical elements, which complicates understanding. Regina even shared her own experience of abandoning a question during an exam that involved graphics because she couldn’t follow the oral descriptions of the multiple-choice options. She stressed the importance of adapting test items during the construction phase, allowing necessary adjustments before the test is finalized, instead of doing it after the test is ready. The current practice, where adaptation occurs after the item is completed, hinders comparability between visually impaired and sighted candidates. Regina also pointed out that Braille reading is slower than visual reading, and the extra hour legally granted for Braille users is insufficient, this time should be longer, according to her. Finally, she noted her discomfort in asking the ledor to repeat readings during her exam, suggesting that a digital reading solution could help avoid such situations, as she would be able to listen as many times as she wanted without depending on anyone.

Christiane brought us the information que her institute has modernized its approach with Braille printers, reducing handmade adaptations and that the current practice involves using adapted images for VI candidates and descriptions when images are not suitable, though handmade adaptations are still needed for complex visuals like paintings or photos. She argues that when images are too difficult to adapt, simplifications or replacements are considered, such as replacing question for more suitable ones. Christiane emphasized the importance of feedback from VI candidates to improve adaptations, though it is difficult to gather feedback directly after tests. Most of the feedback comes through appeals or legal requests, showing a need for better research and communication in this area. In adapting mathematics items, Christiane often collaborates with the question-writing team, but notes that there is no standardized manual for these adaptations, highlighting the need for better guidelines. Her institute complies with Brazilian law on test adaptations and updates options for candidates as new demands arise, such as the recent request for electronic calculator use. Finally, Christiane pointed out that many VI students today rely more on digital materials and descriptions rather than Braille, which is a shift from traditional methods, particularly in the field of mathematics.

Paula emphasized the critical need for specialized training for ledores, using as argument an incident where a student was disadvantaged by a ledor lacking mathematical knowledge. Paula emphasized a decline in Braille literacy among VI students, leading to increased reliance on ledores for test adaptations as well as on screen readers. She also clarified the distinction between test question descriptions and audio descriptions, noting that while audio descriptions are meant for contexts only, like movie scenes, test adaptations require concise and precise descriptions to facilitate understanding without overwhelming the VI candidate. She discussed the adaptation process at INEP, a national institute for research on education, where images are modified to be accessible to VI candidates using computational tools like Easy Braille. However, she pointed out that these adaptations are ineffective for candidates unfamiliar with Braille. Paula identified the adaptation of complex visuals, such as three-dimensional

figures and overlapping two-dimensional shapes, as particularly challenging. Addressing technological needs, Paula suggested the development of specialized screen-reading software tailored for adapted tests to ensure fairness and independence for VI candidates. She also raised the idea of allowing the use of soroban, or abacus, during tests to aid in calculations without providing undue advantages, as soroban does not perform automatic calculations like electronic calculators, rather it works as a paper and a pen to do calculations, meaning that, without the mathematical knowledge, one cannot get answers from the soroban alone. Furthermore, Paula stressed the importance of gathering feedback from both candidates and professionals to continually improve test adaptations. She recommended establishing a dedicated committee to oversee the adaptation process, ensuring that adaptations meet the needs of VI candidates without simplifying the test content. Additionally, she advised that lengthy tests should involve multiple ledores to prevent fatigue and maintain the quality of assistance, especially since candidates with a ledor are granted additional testing time.

As the reader of this paper can see, our suggestions, concerning the improvement of the assessment process for VI candidates, are all based on the expertise of our interviewees, and also on data we analysed on Marcone & Bortolucci (2021). Hence, one of the conclusions that arose from this study is the importance of integrating the adaptation process with the initial construction of assessments. By adapting test items from the beginning, rather than as an afterthought, exam creators can ensure that the necessary adjustments are made to provide an equitable testing experience for VI and sighted candidates alike. This proactive approach is still not widely practiced, and the findings suggest that this change would benefit the VI candidates creating fairer assessments.

Another important issue pointed in this paper is the decreasing familiarity with Braille among younger VI students, the so called “debrailization”, as the VI students are increasingly relying on digital screen readers and ledores instead of Braille itself. It is also important to point out that digital Braille readers are available already, reducing the need for large amounts of paper to print braille. Although screen readers are very important and useful, they do not fully replace the benefits of Braille, particularly in the field of mathematics where precise notation and symbols play a crucial role. The lack of access to Braille materials in educational settings only aggravates this problem.

The interviews also highlighted the importance of the ledor’s role in assisting VI candidates during assessments. The complexity of mathematical language requires ledores who are not only familiar with the subject matter but also trained to provide accurate and neutral descriptions. However, the reality is that most of the ledores are not familiar with all mathematical symbols, reinforcing our argument that, without proper training, ledores risk confusing the VI candidates, hindering their performance. Moreover, the discomfort some candidates feel when requesting repeated readings from the ledor, as stated by Regina as well, shows that alternative methods, such as digital reading tools or recording the audio in advance and providing it to the VI candidate to listen as they like, could provide more autonomy and reduce the reliance on human readers, who are susceptible to errors.

Based on these findings, the study recommends that guidelines should be developed and offered for ledores during a training before acting as such, ensuring that they are adequately prepared. Also, workshops for test creators could be a powerful tool, focusing on designing accessible questions that maintain the integrity of the content while addressing the needs of VI candidates beforehand, instead of working in a hurry, improvising adaptations afterwords. Finally, the creation of a software solution, or a recorded audio, to facilitate digital reading of adapted tests would enhance accessibility and reduce the dependence on ledores, ensuring a more independent and equitable testing process for VI students and less exposure to the possibility of human error.

The adaptation of mathematics assessments for visually impaired candidates requires a comprehensive, proactive approach that begins with an inclusive test development, taking all needs into consideration during the creation of mathematical items, and extends through the testing process itself, been careful with the work of ledores or creating a technological alternative to reduce dependence on ledores. By implementing these recommendations, institutions can better support VI students and ensure that all

candidates are assessed on an equal footing, creating a more inclusive and fair educational experience for all.

Aderaldo, M. F.; Franco, R. P.; De Oliveira, G. T. L. (2020). Introdução à Formação de Audiodescritores: Descrição de Imagens em Provas do ENEM. Revista Linguagem em Foco, Fortaleza,

v. 11, n. 1, p. 97–109. DOI: 10.46230/2674-8266-11-2940. Disponível em:

https://revistas.uece.br/index.php/linguagememfoco/article/view/2940. Acesso em: 26 ago. 2022.

Machado, L. V. A. (2020). Ação de Ledores Diante de Questões de Matemática em Avaliações Públicas. Tese de Doutorado. Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro. Instituto de Matemática – PEMAT. Disponível em: DSc_10_Ledo_Vaccaro_Machado_1.pdf (ufrj.br). Acesso em 14 dez 2022.

Oliveira, M. V. M. (2017). Acessibilidade e ensino superior: desvendando caminhos para ingresso e permanência de alunos com deficiência visual na Universidade Regional do Cariri - URCA sob a perspectiva da avaliação educacional. Disponível em: http://www.repositorio.ufc.br/handle/riufc/30744. Acesso em 26 ago. 2022.

Oliveira, T. M. S. [et al.]. (2021). Guia de introdução à audiodescrição didática para docentes. Guarulhos: IFSP Campus Guarulhos. Disponível em: https://educapes.capes.gov.br/handle/capes/700372?mode=simple. Acesso em: 26 ago. 2022.

Vieira, M. E. M. Recursos utilizados por estudantes com cegueira no Ensino Superior e o possível processo de desbrailização. Revista Instituto Benjamin Constant. V. 28, n. 64 (2022) -. Rio de Janeiro: Divisão de Pesquisa, Documentação e Informação. Disponível em: Recursos utilizados por estudantes com cegueira no Ensino Superior e o possível processo de desbrailização | Benjamin Constant (ibc.gov.br). Acesso em: 20 de dezembro de 2022.