Introduction

This paper aims to clarify the content of our concept of resistance. To achieve this target, the main theoretical inspiration will be taken from the philosophy of Ernst Bloch and exemplifications will be drawn from Latin-American feminism, science-fiction and crime TV series1. If only one starts to think of it, resistance reveals a slippery and elusive nature. To be sure, it reveals a very pervasive concept that can be said in many ways just as well as being. Indeed, it occurs in electromagnetism as the measure of an object’s opposition to a certain flow of electric current; in human history as the physical and moral endurance in warfare and contestations; in political philosophy and jurisprudence as the right to contrast illegitimate authority; in physical exercises as the body workout against weights, bands or forces; and so forth (Del Sordo 2021).

Recently, resistance has also joined the shortlist of concepts of theoretical philosophy where resistance has been numbered among the attributes of phrónesis or practical wisdom. In this respect, I think the book José Medina's Epistemology of Resistance (2013) has been pivotal. It develops, indeed, virtue- based ethics of knowing that evolves around the idea of resistance considered as a kind of dianoetic virtue, i.e., as an admirable character trait that any epistemic agent should nurture. In this context, an epistemic agent is said to be resistant when, under conditions of oppression or disadvantage, he or she manages to gain momentum and put into doubt eventually interiorized feelings, or self-convictions, of inferiority.

Resistance thus emerges as a counteractive force that reacts against material, physical, political, epistemic or intellectual forms of oppression. I will refer to this aspect of the concept as the resistance tout court. Such a relational characterization does not seem, however, to be fine-grained enough to wholly identify what we mean by resistance. Medina 2013 seems to refer to a more complex phenomenon than resistance tout court. I will refer to the more complex phenomenon of resistance as hope resistance2, whose particular outline runs from Ernst Bloch’s idea of hope principle.

Hope resistance is a hybrid concept that defies hypostatization and abstractions (Thomason 2013, p.12), forcing philosophers to undertake approaches that are contextual and performative. In his visionary trilogy, Bloch never resorts to analytical principles or positive exemplifications. Rather, he tends to use negative examples and make the readers acquainted with hope through guided jumps of comprehension. Regrettably, Bloch is never mentioned by Medina 2013, either in the text or in its bibliography. To clarify the concept of resistance, Medina recalls illustrious examples of resistant heroes and heroines, e.g., Juana Inez de la Cruz and Rosa Parks.

Without clarification of the abovementioned distinction between resistance tout court and hope resistance, the exposition through exemplary figures runs the risk of being misunderstood or unserviceable. Discourses about science fiction and crime TV series may provide us with illustrative examples of this eventual kind of misunderstanding (Cambra Badii 2018).

1 The fruitful application of case studies from TV series in philosophical and psychological investigations has been supported and expounded in Cambra Badii 2018.

2 McDonald, Stephenson 2010 interestingly couples the concept of hope with that of resilience, which shares lines of affinity with that of resistance. Also, for an embedding of hope into virtue epistemology and ethics one could consult Billias 2010.

The audience of sci-fi and crime series seems, indeed, to behave ambivalently3. Hooked spectators follow the plots and heartly cheer for Lacie in Nosedive (Brooker 2016), Becky or Jessica Hyde in Utopia (Kelly, 2013-2014) or The Professor in Money Heist (Pina, 2017-2021). They seem to understand their heroes’ reasoning, supporting their deliberations against the grain. While being sympathetic with them, the audience seems contemporarily unable to produce any real corresponding resistance in their routine way of using digital and medical technology or of being involved in worldwide financial machinery. Following my distinction, however, there might be some conceptual confusion in interpreting this behaviour in terms of ambivalence.

Social or individual changes can be the effects of either resistance tout court or hope resistance. Accordingly, the fact that the audience's aversion to digital technology is not manifestly transferred from the fictitious to the real world cannot stand for a neat absence of resistance in it. One can interpret this absence in terms of resistance tout court, which does not imply on its own a vanishing of hope resistance too.

This paper follows this outline. The first and second sections are dedicated to the introduction of the idea of hope resistance. In the first section, I will introduce the concepts of utopian function and anticipation drawing upon the first volume of Bloch’s 1995 trilogy. In the second section, I will draw inspiration from the heroine Juana Inez de la Cruz to exemplify utopian function and hope resistance. In the fourth and fifth sections, I will show that characters of Black Mirror, Utopia and Money Heist bring to light aspects of hope resistance. I will conclude that corresponding appearances of ambivalent behaviours deserve more fine-grained recalculations

Utopian Function and Anticipation

Ernst Bloch has been numbered among traditional authors of future philosophy. Indeed, one can find a brief, but satisfactory, account of his future ontology in Poli 2017. Bloch’s discourse on hope is layered along interwoven levels of analysis involving biology, affectivity, ontology and epistemology.

The hope principle begins with a kind of processual and biological monism, where modification, openness and change figure out as ontological pillars. Life in itself is an immediate condition where

<<That we are alive cannot be felt>>.

That which posits us as living does not itself emerge. It lies deep down, where we begin to be corporeal. […] Nobody has sought out this state of urging, it has been with us ever since we have existed and in that we exist. The nature of our immediate being is empty […] all of this does not feel itself, in order to do so it must first go out of itself (Bloch, 1995, p. 45)

The mediate condition of life, namely, where life feels itself, arises as a ‘vague and indefinite’ thirst that urges immediate life to “go out of itself”.

For one thing, Bloch sternly defuses the search for fundamental human drives (Ibid. Ch. 13). He indeed criticizes philosophers and psychologists positing as fundamental either sex, power, eros or archetypes. According to him, fundamentality is always biased by contingent constraints, mainly socioeconomic, that deceive our inquiries with false promises of absoluteness. For another thing, he determines two drives that can notwithstanding aspire to be more basic than others. The two seemingly fundamental drives are preservation and completion4. Preservation must be interpreted as an appetite for appropriate conditions of life unfolding. Completion must be interpreted as a drive towards ongoing perfection.

3 The behaviour of TV series spectators can be considered a technological extension of human behaviours. Along this line, the embodiment relation of technology with the users, taken as living bodies, has been analyzed in Liberati 2019, Bonfiglioli 2021. In this respect, further insights to deepen can be found into the imaginative resistance phenomenon (see Tuna 2020). For the general philosophical relevance of fiction and the variety of theories thereupon see Aldegani 2021.

4 For an ontological view of completion see Žižek 2013.

Preservation and completion are filled in by affectivity, which is a qualitative and situated condition of living matter. As soon as the process of “going out of itself” takes place, drives give rise to vague intentional acts of striving and longing without distinct intentional objects (ibid. p. 45). These acts can be further refined and streamlined in full-grown intentional acts, with their own distinct objects. The refinement of the acts of striving and longing constitutes what Bloch calls desiderium (ibid. Ch. 10).

In addition to the satisfaction of particular desires, a general unsatisfied desire is always residual. Residuality brings about the distinction between filled and expectant affects (ibid., p. 74). The former is "short-term", that is, their intentional drive object lies in the "already available" world. Envy, greed, and admiration are kinds of filled affects. Expectant affects instead are "long-term", that is, their intentional drive object does not lie yet ready, either in the respective individual attainability or in the already available world (ibid., Ch. 13). Examples of expected affects are anxiety, fear, hope or faith.

At first glance, the distinction between filled and expectant affects seems odd. Bloch indeed classifies hope among the expectant affects, but to be sure, one’s hope can be directed towards short-term objects as well. In addition, I would say, it is usually so. For instance, I can hope that tomorrow will be sunny or that the war in Ukraine will not break out. Which objects can expectant hopes be oriented to?

According to Bloch, traditional ontology and epistemology have usually dealt with bounded objects, that is, objects whose identifying content, function or machinery, even though unknown, are already established. Bloch's objects claim to be open in this respect. According to him, what we usually call an "object" is just the contingent and socioeconomically constrained endpoint of a wider ontological wake of its possible configurations.

Traditional ontology and epistemology make historically determined cuts along ontological wakes. This would not be a problem, however, if only one is ready to admit that the cut is a matter of temporary convenience and is prompt to hand again full ontological wakes to objects themselves. Unfortunately, this readmission hardly surfaces and what were just convenient cuts are likely to become tough constraining boundaries.

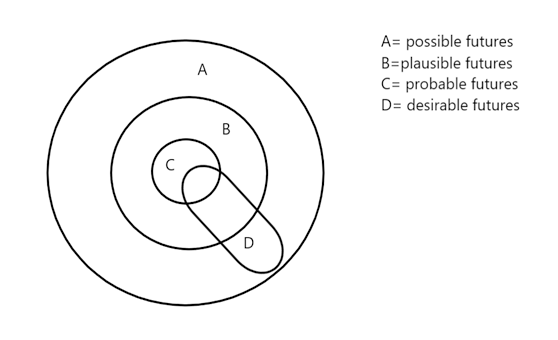

The removal of ontological boundaries opens up the real possible horizon of an object. Real possibility involves at least four kinds of futures, namely, desirable, probable, plausible and possible futures (Poli 2019, Ch.10). The desirable future of an object, say x, includes those not-yet configurations of it that we would prefer to live with. Probable futures are the not-yet configurations of x that are in line with our current social constraints, habitus or trends. Plausible futures are the not-yet configurations of x that are in line with the current state of our knowledge. Possible futures are all the configurations of x that we can materially, or even only abstractly, imagine.

It is important to notice that desirable futures give rise to a cross-section of the other kinds of futures. That is, a future configuration is desirable regardless of its similarity or dissimilarity with what is probable or plausible. Desirable possible futures make up what Bloch calls ‘the immense utopian field of the world’ (Cf. Bloch 1995, p.6). Expectant affects are usually directed toward possible futures, there lying long-term objects, while filled affects are usually directed toward plausible or probable futures, there lying short-term objects.

Desirable, probable, plausible, and possible futures are ordinated by inclusion and intersect as follows:

Figure 1. Intersecting Futures

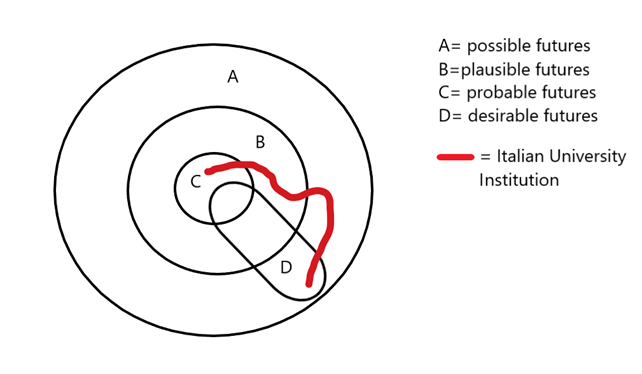

We may imagine now that an object draws a line along the intersecting futures. For instance, we may imagine that the following red line is drawn by the Italian university institution:

Figure 2. The Line of an Object along Intersecting Futures

Along this line, the Italian university institution finds a desirable future only in the realm of possibility and utopian field. This means that its desirable configurations are very long-term and that a desire

directed toward it is expected to exert what Bloch calls utopian function, which is filled in by expectant affects (Bloch 1995, p.115, passim).

The utopian field becomes epistemically accessible by stripping away from the objects their acquired boundaries. The blowing up of historically determined boundaries liberates from the objects an almost blinding beam of light. This liberated light constitutes the phenomenon Bloch calls “resistance of the novum” (ibid. p. 128-32). The novum arises here as something merely determinable that must be informed and determinate, not even without difficulties, to be bestowed with an anticipatory role that succeeds in driving our actions.

We can get acquainted with the blinding light of the novum by taking into account what is like to experience the epistemological scope of the hope principle. The epistemological aspects of the hope principle are in plain contrast with what is called the contemplative paradigm (ibid) of knowledge. The contemplative paradigm currently dominates knowledge. It sets the results of cognition back as a premise of cognition itself and refers to some already-established being of the object of knowledge. Upon closer inspection, this assumption is already implicitly present in our cognitive life, both in our common sense and in our scientific or philosophical-systematic endeavors. Let me point out a couple of examples. If I see my desk, I know that I’m seeing it as it already is and as it were tonight before I woke up. If I see a star, I know that I’m seeing it as it had already been several years ago.5 If I give proof of the Pythagorean Theorem, I'm implicitly assuming that the ratio of the legs identifies a property of the hypotenuse as it already is and not as it is going to become or as it has not yet become. Hence, it is no easy task to imagine or visualize any change in the contemplative paradigm of knowledge. This novelty would be a total breach of our cognitive habitus, thus showing that kind of resistance to determination that according to Bloch is typical of the new and the determinable.

Anticipation arises as a practical utopian activity or a militancy toward the novum. The practical facet of anticipation makes up the cornerstone of nowadays future studies6. Anticipation allows us to gradually work out the dialectics between the determination and the determinability of the novum. Following the hope principle, we have a biological impulse to anticipate the novum instead of passively waiting for its realization. This impulse would be encoded within the fundamental drives to preservation and completion.

In the next section, I will draw an example of utopian function from the original Mexican feminism.

The Case of Sor Juana Inez de la Cruz

In seventeenth-century Mexico, Juana Ines de la Cruz felt a strong desiderium towards knowledge throughout her life. Now, following Bloch’s perspective, knowledge, like any other object, is encapsulated in a social narrative that confines it and its reachability within specific boundaries.

Knowledge was out of Juana’s reach because of her contemporary narratives. First, she was a young woman and thus could not go to the University of Mexico City. Then, she became a nun, and thus, she couldn’t have masters to teach her arts, literature or sciences. She had to spend most of her time after monastic stuff and could dedicate only spare time to her lay inclinations.

5 In the cognitive sciences, these two examples are reflected in the causal theory of perception.

6 <<Anticipation consists of two elements: a model and its translation into action. Looking at the weather forecast is not an anticipatory activity in itself, but deciding to take an umbrella as a result of what you have seen is. Forecasts are nothing more than a model, they just tell us what could happen. Having seen what could happen and changing one's behaviour accordingly is a case of anticipatory activity. Still, anticipatory behaviour is more robust than reactive behaviour, i.e. waiting for something to happen and then responding. Reactive strategies are expensive and inefficient: they are a sure recipe for failure. There are no valid alternatives to a forward-looking approach. If anything, the point is to understand that there are many different ways of anticipating and that it is necessary to find those that are best suited to one’s situation; just as it is necessary to understand the cognitive and social constraints that filter and condition the translation of a model into action. (Poli 2019, p. 14-5)

In a letter to Sor Filotea, Juana said that her longing for arts, literature and sciences was so strong that she never succeeded in burning it off:

What is true is I will not deny [...] since the first light of reason beamed on me, my inclination towards letters was so vehement and powerful, that not even outside reprimands --which I have had many--, nor my reflexes --which I have done quite a few--, have been enough for me to stop following this natural impulse God placed in me (Cruz 1994 p.10). [translation mine]

As it seems, Juana’s desire for knowledge was hard to eradicate. Rather, it grew up stronger, as soon as one tries to remove it (ibid. p. 12). As is clear in the letter, Juana started studying humbly following her only feasible routes. The drive for knowledge was so strong to allow her to put into brackets even her socially acquired feeling of inferiority7. By designing her path, Juana opened up the ontological boundaries of knowledge. With this move, she put into question a wholesale received view of knowledge according to which knowledge is a kind of Russian doll made up of specialized disciplines encapsulated one in the other.

According to her contemporary dominating narratives, the study of theology was conceded only to students who were previously trained in specific disciplines. This condition was unaffordable for Juana, who strives for knowledge alone and without libraries, masters or disciples.

Despite her difficulties, Juana started studying specialized disciplines just by reading the books she happened to have and along the order she could. Along this path, she surprisingly discovered otherwise unforecastable facets of knowledge. In particular, she experienced that knowledge was not at all divided into encapsulated sectors. It was rather horizontal and allowed students to learn disciplines through free wandering from one sector to the other. Music, for instance, might allow Juana to understand history, cooking chemistry, poetry mathematics, and toy physics.

And so, by having some principles gained, I continually studied various things, without having any particular inclination, but rather all in general. Therefore, having studied some in more detail than others has not been my choice, but rather the chance of having come across more books of those faculties has given them, without my deliberation, the preference. […] True, I say this about the practical part […] because it is clear that while the pen moves, the compass rests and while the harp is played, the organ calms down, et sic de caeteris; […] but in the formal and speculative the opposite happens, and I would like to persuade everyone with my experience that not only do they not get on the way, but they help each other by giving light and opening the way for one another, through variations and hidden links [...] in a way that seems to correspond and are united with admirable bonding and concert. […] I can assure you that what I do not understand in an author from one faculty, I usually understand in another from another that seems very distant; and those own, when explained, open metaphorical examples of other arts […]. (ibid. p. 13- 14, translation mine)

Well, what could I tell […] about the natural secrets that I have discovered while cooking? I see that an egg is united and fried in butter or oil and, on the contrary, it breaks apart in the syrup; […] If Aristotle had cooked, he would have written much more. (ibid., p. 24, translation mine)

Juana’s strong desire for knowledge led her to reshape the boundaries of this object, drawing materials upon the utopian field of desirable possible knowledge. The example of Juana also allows us to illustrate that the anticipatory militancy ignited by utopian function conveys withstanding capacities in front of even adversary present conditions.

As might be clear, Juana’s resistance is not just resistance tout court. It is not just a matter of maverick keeping on or giving something up. Juana was concerned with the ontologically subversive endeavor of

7 For the importance of self-trust in fighting against epistemic injustice see El Kassar 2021.

opening up knowledge boundaries to utopian horizons of new configurations8. Because it involves such a utopian function, Juana’s resistance can be considered a true example of hope resistance.9

In the next section, I will analyse the characters of Lacie in Nosedive and Becky in Utopia. I will also show that their resistance is hope resistance.

Hope Resistance in Science Fiction TV Series

This section identifies elements of hope resistance in science fiction TV series. There are, I think, at least two cases deserving discussion. One is Black Mirror10 and the other is Utopia. The episodes of the former breach the banks that digital technologies massively impose on human life emotions. The second blow up the fixed contours and limitations that massive biotechnological medicine superimposes on the quality of human living conditions.

Both series display examples of hope resistance. Some of their protagonists do not just strenuously reject digital technologies or massive biotech sanitary treatments. Rather, they reshape the current boundaries of human health and satisfaction.

The first example of hope resistance I want to draw attention to comes from Nosedive, a very well- known episode of the highly frequented TV series Black Mirror. In Nosedive, the protagonist Lacie Pound aims at feeling content with herself and up to the level wherever she winds up in. Unfortunately, however, she finds these targets confined within the reluctant dominating narrative of a network of digital social ratings.

Lacie lives in a society where private citizens, politics, enterprises, etc., do such intense use of a digital social rating network that one cannot rent a house or a car or cannot get access to medical treatments unless she has at least a certain score, 4.5 for example. Lacie strives to be highly scored, but ironically, the more she strives for it, the lower score she obtains. As a result, she always ends up being frustrated. Her most desirable future is somehow trapped and locked in a cage whose key was momentarily unavailable to her.

The bet of hope resistance on Lacie consists of constructing another narrative around contentment and personal adequacy. If Lacie exerted only resistance tout court, she would have just thrown the smartphone away without diminishing, or rather worsening, her grade of frustration.

Luckily, Lacie succeeds in discovering the liberatory power of utopic functions, thanks to her getting into acquaintance with Susan. Susan is a middle-aged truck driver and plain woman, appearing amid a highly trafficked railway. She scored very low. However, despite it, she is content with herself.

Susan's contentment does not depend on her resistance tout court. She has not just abandoned the social network Lacie was fond of. Susan has rather conquered a utopic scenario where her being adequate and content undergoes reconfiguration. Contentment and personal adequacy accordingly change their contours, becoming independent of any digital rating mechanism.

8 The interlace between resistance and epistemic academic narratives is investigated in Bonfiglioli 2020 focusing on Covid19 pandemics.

9 Medina’s analysis of Sor Juana brings about themes that are close to the ones I have so far outlined: << Despite Sor Juana’s constant critique of epistemic arrogance and constant (even excessive) exercises of humility, she argues that we should not get discouraged by the difficulties and dangers involved in the pursuit of knowledge. For, no matter how extreme these difficulties and dangers may be, they make the journey and its achievements all the more valuable; and it is ultimately up to the subjects themselves (regardless of their gender identity or sexuality) to decide whether they are up to the challenge and whether the epistemic risks are worth taking. […] Our experiential perspectives can be broadened with our capacity to imagine, to survey possible worlds in which alternative experiences can be had. This kind of imaginative knowledge has a crucial counterfactual dimension: even if the actual world does not allow certain experiences to be had, their possibility can be used as the basis of alternative knowledge, an epistemic counterpoint to lived experience and knowledge, which is still grounded in real life and embodied experiences>> (Medina 2013, p. 232).

10 For a detailed discussion on Black Mirror and its relevant bibliography from the specialized point of view of film theory, one can consult the recent paper Sorolla-Romero et al. 2020. For a philosophical perspective on the same series, consult Johnson 2020.

Well, Susan's life choices are echoed in Lacie. She starts doing the same, not caring for the scores and being brutally sincere with all people. Brutal sincerity renders Susan and Lacie marginalized women, who fiercely withstand their marginalization. They may bear it so stoically because they cherish the utopic idea that contentment and adequacy can finally be liberated from chains of oppressive digital rating narratives. From this perspective, current marginalization thus arises as working anticipation of positive possible futures. Susan and Lacie militate in this utopic direction, thereby withstanding any current social rating without running the risk of being trampled to death of social frustration. The example of Nosedive support us to recognize that anticipatory practices may foster the capacity of people to reinterpret present bed conditions in term of weak signals (Poli 201911) of a positive upcoming blossoming future.

Utopia is a less-known work than Nosedive. It was launched in 2013 on an English channel and then canceled because of purported image crudity. In 2020, Utopia was remade by Amazon. The 2013 original and the remake are quite different from each other. Up to the present, I didn't get the occasion to properly appreciate their differences. In this paper, I thus refer to the original 2013 version.

Utopia has a highly entangled plot. This aspect is underscored also by the fact that the final episode contains a hint of a never-released continuation. Utopia refers to a project of DNA selection, called Giano, developed by Corvardt, a pharmacy industry. Through Giano, Corvardt works on the project of decreasing the human population by spreading a seeming vaccine produced for confronting purportedly dangerous illnesses. In the fight against Giano, all the characters of Utopia display the traits of resistance tout court. Nevertheless, the series also offers examples of true hope resistance.

Jessica Hyde, for instance, is an unforgivable hope-resistant character. However, her vague traits of insanity render her analysis both slippery and critical. For this reason, I prefer to allocate her analysis to contributions tailored to Utopia. The character of Becky better serves the purpose of this paper.

Becky is a Ph.D. candidate in medicine. She apparently suffers from a degenerative illness called Diel's syndrome. From the beginning of the series, it is clear that Diels syndrome could be a genetically transmissible illness arising at the core of Giano. Becky suffers from spasms and epileptic attacks. She knows she could only delay these symptoms by taking a pharmakon called Thoraxine.

Becky desires to discover the truth about Giano and her related illness. At the end of the series, she finally determines at least part of that truth. In particular, she discovers her illness was not an illness properly. Spasms and epileptic attacks are negative side effects of Thoraxine itself, which turns out to be an opiate. She gets access to this truth as soon as she refuses to take Thoraxine. This action of refusal encodes elements of resistance tout court. It remains clear however that Becky’s is a more complex turn12.

First, her turn is deeply motivated by suspicions of the Corvardt project and the mainstream political narrative about it. Second, it is supported by an anticipatory jump to a utopic future where the acquired view of techno-medical health blows up. Putting it in Bloch’s terms, Becky liberates the novum along the ontological wake of human health. According to such novum, health passes from being a function of pharmacology and technomedicine to a proper function of human bodies.

Becky’s trajectory reveals another aspect of hope resistance. This aspect is something we may call a

debunking power of hope resistance. Indeed, hope resistance, with the aid of epistemic suspicion, may

11 <<Weak signals are born and die all the time. There are a lot of them, but their patterns are difficult to see and interpret because they are weak. Only a few can consolidate and become new trends. Since they are not generally appreciated by decision-makers, a naive approach to weak signals is doomed to fail. Asking a person to pick up a weak signal is like asking them to point out something irrelevant that might be relevant. They are usually recognized by pioneers or special groups, rather than by recognized experts. To intercept them it is useful to work with the future. natives, those who adopt new technologies first, who question the paradigms, and who create the future themselves>> (Poli 2019, p. 75 passim).

12 A detailed account of the performing relationship between hope, on the one hand, and therapy, suffering and medical practices, on the

other, can be found in Waterworth, Chs. 5,4 and Haramati 2010.

help people liberate themselves by demystifying certain narratives and opening up new explanatory horizons.

Becky's epistemic manoeuvre would have been out of her reach if resistance was restricted to resistance tout court. The strength of Becky’s turn does not lie just in the act of giving up with her counterproductive pharmakon. Rather lies in a subversive and jumping act of anticipatory hope that brings her close to authentically new working paradigms for human health conditions.

In the next section, I will draw examples of hope resistance from a well-known case of heist crime TV series.